For raw ales, as with any beer, the sky is pretty much the limit when it comes to flavoring ingredients, but there are some that are more common traditionally than others.

Brewing Nordic Farmhouse Raw Ale: Part 1

The concepts of raw ale and Nordic farmhouse yeasts first worked their way into my head when researching historical brewing for my first book Make Mead Like a Viking. I began to experiment more in-depth when I began to focus more on beer brewing for my second book Brew Beer Like a Yeti. It seemed that as I delved deeper into this fascinating subject, my yearning for knowledge just kept growing. The rabbit hole was long and deep…and very, very old.

Zen and the Smell of Cow Manure in the Morning (Revisited)

During one of my early-morning road bike rides through the rolling hills of Berea, Kentucky, I found myself contemplating random thoughts, as I usually do to distract myself from the burning of my leg muscles, the cramping of my wrists and the unpleasant feelings in my posterior. Riding past a cow pasture, a common occurrence, I realized that I actually enjoyed breathing in the smell of cow manure in the cool morning air while whizzing past herds of lumbering cattle.

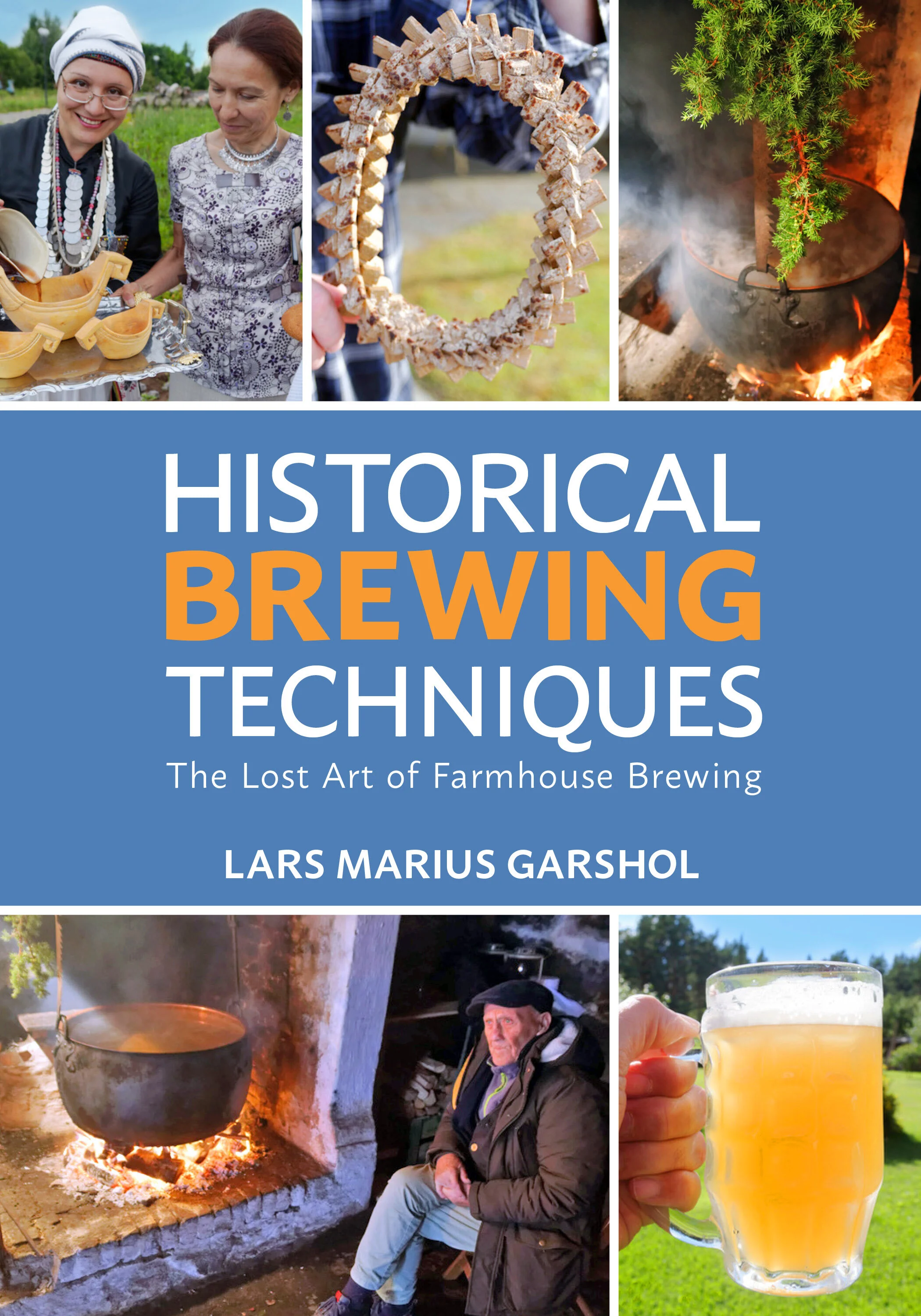

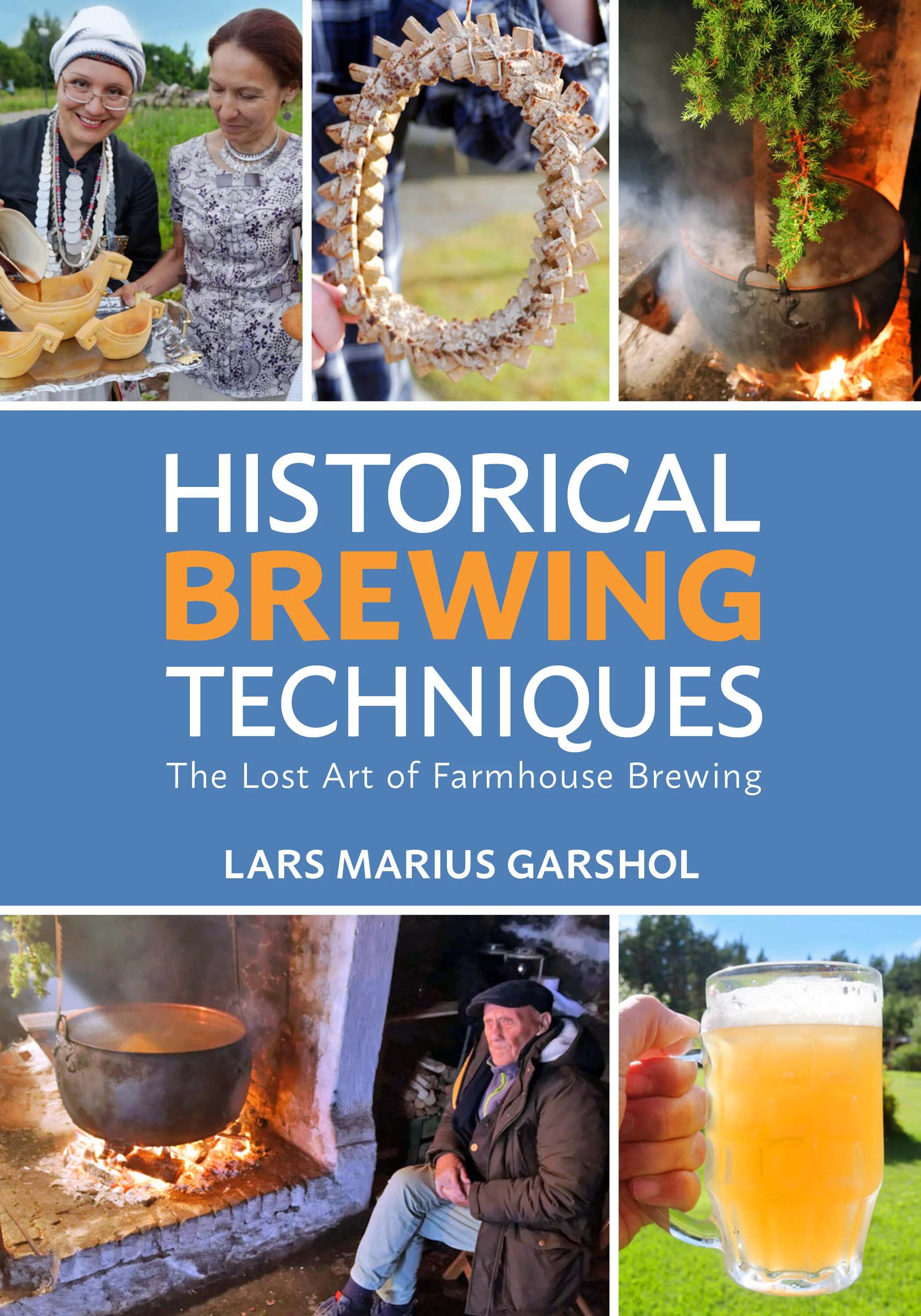

Historical Brewing Techniques: Part 2

In the first part of this series, I conducted an interview with Lars Marius Garshol, author of Historical Brewing Techniques: The Lost Art of Farmhouse Brewing and the blog Larsblog. Read on for my review of Historical Brewing Techniques and some thoughts it brought up regarding this completely “new” ancient style of brewing.

While Historical Brewing Techniques covers a lot of the same territory as Larsblog, this is by no means a bad thing. Not only is Garshol’s research now in convenient bound form (it’s a sturdy 400-page tome with nice glossy pages for the inevitable beer spillage), but the information from his blog is greatly expanded on. I recommend enjoying it like I did, on the back porch with a beer or three. For my first read-through I made some notes on pages I wanted to come back to when I was ready to start applying the wealth of knowledge contained within, but mostly I just enjoyed the narrative. Even those with little interest in the subject matter can appreciate the book for its engaging combination of travelogue, history, folklore, and fascinating data-driven research. Garshol has uncovered a vibrant brewing and drinking culture that has quietly continued in far corners of Europe (and some not so far corners) while modern, commercial brewing grew to monolithic proportions in much of the world.

Much of what goes on in the craft brewing and homebrewing worlds, even with so-called “farmhouse” styles, relies on tools, techniques and temperatures that are considered irrefutably crucial in creating good beer. (There are definitely some exceptions, though.) Garshol makes it abundantly clear that much of this dogma is antithetical to how people brewed in the days when nearly every household brewed their own beer from start to finish. As a matter of fact, he goes so far as to say that modern commercial brewing and rustic farmhouse brewing should really be thought of as completely separate categories, as they have “evolved separately, drifting apart over many centuries [279].”

Beers brewed by the methods outlined in this book employ vastly different processes and ingredients than commercial beers, and can thus can differ greatly in flavor. If you’re a brewer who is a stickler for the “absolutely necessary” specifics that have been hammered in throughout the modern brewing literature, you’ll need to take a deep breath before delving in. Following is just a sample of the brewing heresies that Garshol discovered farmhouse brewers regularly commit:

A different outlook on cleanliness. Farmhouse breweries can be a far cry from modern, super clean and sanitary commercial (and home) breweries. With many literally being on farms and often using wood as a heating source, the brewing area can often be dank, dusty, and sooty. Except for those who have started incorporating modern brewing into their practices, sanitation with modern chemicals just doesn’t happen. This doesn’t mean that they’re not very aware of possible beer spoilage. Cleaning equipment is an important part of the brew day as with any other brewer; they just employ very different methods. For some brewers, one of the first steps in a brew day is to make up a juniper infusion by boiling juniper branches in water. This infusion is often used as the strike water for drawing out sugars from the mash, but it is also used to clean equipment. While they are very careful about cleaning, farmhouse brewers historically didn’t actually know for sure what kept beer from going bad, so they developed rituals and superstitions that they were sure to follow extremely carefully with every batch. If nearly every beer they made turned out good following these steps, and it worked for their father, mother, grandfather or grandmother (and their ancestors), then it must work.

Preparing a juniper infusion. Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol, from Brewing raw ale in Hornindal.

The wort often isn’t boiled. One of the most fascinating aspects of farmhouse brewing, and one of the core elements that enables such unique flavors, is the concept of raw ale. As a brewer who adhered closely to modern brewing “necessities” when I first read of raw ales, I had a hard time believing that you didn’t need to boil wort when brewing beer. But if you think of the reasons we boil wort when brewing, and look at it historically, this makes perfect sense. For one, we get all of those bitter and aromatic flavors from hops in modern beers such as IPAs through a process called isomerization. Without the proper equipment, and a consistent source of high heat, boiling wort for 60 minutes or more just wasn’t possible historically. While many farmhouse brewers do use hops, they’re not used the same way as in modern beers. They understand their antibacterial properties, but most don’t use them for flavoring. If hops are used, they’re made into a hop tea that is added to the wort while lautering, or even to-taste when drinking. Juniper and various other herbs are known to have antibacterial properties, and were often used instead of, or along with, hops. As Garshol notes, though, there is a broad spectrum as to how these ingredients are used and whether there is no boil, a short boil, or a long boil (of the wort, that is; boiling the mash is also a technique some brewers use).

A mug of raw ale. Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol, from Raw Ale.

A general lack of temperature monitoring and precise measurements. For many of the brewers Garshol interviewed, he was surprised to find that thermometers were rarely used and that they just eyeballed ingredient measurements. In modern brewing, if we want to achieve a particular flavor, alcohol level, and other factors that make for a specific style, it is important to be precise. Most farmhouse brewers aren’t brewing a “style,” they’re just brewing the same type of beer that they were taught to brew by the previous generation. Although there may be nuanced differences between batches, they pretty much make the same beer every time. Because of this, they can judge the proper temperature and ingredient amounts just by look, feel and taste. Some of the brewers Garshol interviewed were perplexed as to why anyone would want to take precise measurements, while others were almost mocking of the modern brewing world’s obsession with precision.

Terje Raftevold brewing by instinct and tradition in Hornindal, Norway. Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol from Brewing raw ale in Hornindal.

The yeast; oh, the yeast… An entire book could be written on the yeast used in farmhouse brewing and how it is utterly different from how pretty much any other modern yeast works. Garshol dedicates a good portion of his book to discussing farmhouse yeast, although he admits that there is much more to explore. His discussion on yeast focuses heavily on the current darling of the brewing world, kveik, but he discusses other yeasts as well. Kveik itself, which simply means “yeast” in some Norwegian dialects, has many variants. Other words used for yeast include gjest(er), gjaer and berm. And then there are the words used in Sweden, Denmark, the Baltics, and other countries. Since each region—even individual farmhouses—had their own unique yeast, there are a plethora of nuances in yeast behavior. Garshol feels he has only touched the tip of the iceberg, but he still covers an impressive amount of ground. If we just consider kveik, some of the ways in which its behavior differs from modern yeast include pitching temperature (often 90 degrees F / 32 C or higher); fast fermentation (full attenuation in as little as 48 hours); viability (many strains have been saved and re-used with little-to-no bacterial infection in non-sanitary conditions for generations—people generations, not just yeast generations); and unique flavors (many contribute citrusy, tropical flavors). The saved yeast isn’t subjected to anything resembling laboratory analysis, and is stored by methods such as refrigerating slurry in glass jars, setting it out to dry and then saving the dried chips in plastic baggies, or even dropping a yeast log, yeast ring or cloth into actively fermenting beer, which is then simply left in a rafter or some other “unsanitary” place to dry until the next use.

Terje Raftevold harvesting kveik after 40 hours. Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol from How to use kveik.

I could go on and on about the many other fascinating aspects of this book, but you’ll just need to read it yourself. In addition to some solid technical how-to and recipes, we’ve got history, folklore, superstitions, yeast-waking screams, oven beers, and some rather interesting malting practices. If you don’t believe me when I say just how unique this book is, how many other brewing books are out there that list as part of a recipe to scream loudly or say the name of every angry dog in the neighborhood? I warrant you there aren’t many…

Historical Brewing Techniques: Part 1

In this 3-part series, I will be exploring this book and the avenues it opens up for changing the face of modern brewing by stepping back in time. First, I will be presenting my interview with Garshol on his new book, followed by my review of the book; then I will cover my explorations in brewing with the techniques, ingredients and yeasts I was introduced to by Garshol and Laitinen.

2019 Viking Brewing Tour: A Photo Recap

2019 Viking Yeti Beer Tour

I’m excited to be headed to the UK! I’ve got several events planned in the short time I’ll be there. First, I’ll be heading to Manchester in northern England for a brew day and book signing at Beer Nouveau. England’s smallest commercial brewery, Beer Nouveau is my kind of brewery. They eschew modern conventions and look to recreate traditional “heritage” beer styles.

Wild Yeast is Your Friend

A Very Meadly Travelogue

Celebrate Yule Like a Viking

Make Mead Like a Viking is Finally Here!

It's finally here! I don't know about you but I'm glad to be able to stop saying it's almost here and have a physical product to show off. Big kudos to my publisher, Chelsea Green Publishing, for all the work they did in putting together a beautiful product. The words within will speak for themselves but I'm thrilled with how amazing the final product looks. Click here for information on how to order your very own copy. Although I fully support independent booksellers and publishers, Amazon rankings are a big deal, so wherever you buy it, please review it on Amazon and elsewhere.

My event schedule is booking up quickly. Stay tuned for 2016 workshop and book tour information. I presented at the Mother Earth News Fair in Kansas recently. I received a lot of wonderful feedback, and signed some books (see photos below). Coming up (very) soon, I'll be doing some local signings. On Wednesday, November 4 from 6 pm to 7:30 pm, I'll be celebrating the book's official publication date with a signing and a reading at Robie Books in my hometown of Berea, Kentucky. You can find information at the Facebook event page. I'll also be signing at the Berea College Store along with other alumni authors during the Berea College Homecoming on Friday, November 13 from 12 pm to 5 pm and Saturday, November 14 from 10 am to 1 pm. Finally, I'll be teaching a workshop on how to make a simple "small mead" flavored with holiday spices that attendees will brew on site and will be able to bring home and drink in time for the holidays. See here for details.

Hope to see you at an upcoming event. Keep on meadening!

Mother Earth News Fair Book Release Event

I've been busy finishing up the final edits to the proof of Make Mead Like a Viking, and am wrapping up articles for Earthineer, New Pioneer magazine, Backwoods Home magazine, and who knows what else. I have a brief breather now that most of my work is off to be looked over by editors, proofreaders and other folks I'm lucky enough to work with, so I thought I'd touch base with you good people before the next round of craziness starts.

The upcoming year is looking to be a life-changing one for me as my book and other new writings begin to make the rounds. I'm excited, and certainly a bit nervous, but the feedback I've been hearing so far has been positive. That should make everything okay, right? One thing that has me particularly stoked is that the first review that came in from the advance copy (for inclusion as a "blurb" on the book inside and/or back cover) is from the "Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines, and Extreme Beverages" himself, Patrick McGovern, the author of Ancient Wine and Uncorking the Past:

“Jereme Zimmerman has captured the wild spirit of mead quite literally―as the quintessential naturally fermented beverage of humankind from the beginning, which reached its apotheosis with the Vikings. Without compromising its mysterious allure, he brings it down to earth for all to make and enjoy.”

Mr. McGovern has been a strong influence on my writing and his research has been vital in helping me to learn just how the Vikings might have actually made mead. I've enjoyed some great historical beers from Dogfish Head brewery that were crafted by Sam Calagione in collaboration with Mr. McGovern as well. Now to see what some of the other Big Names currently reviewing the book have to say...

Rather than passing along any more of my recipes for this newsletter, I wanted to give a shout-out to Amber of Pixie's Pocket. I've been taking note of her mead and wine recipes for some of my own fermentation experiments and give them the full Yeti Seal of Approval. Her Vanilla Bean Chamomile Mead and Mint Wine recipes in particular are on my to-do list.

That's it for now. Be sure to scroll down for updates on my upcoming workshops, including my official book-release workshop at the Kansas Mother Earth News Fair...

Upcoming workshops and speaking engagements

This reclusive hobbit-yeti will be leaving his hobbit hole soon for a grand adventure. I'll be promoting my book and spreading the word about the wild-mead movement over the next year and beyond. Here's what I have for now but who knows where I'll be next...

Downtown Richmond (Kentucky) Farmers Market, August 22, 10-12 am

Sorry about the short notice on this one. Yes, it is this coming Saturday. I'll be doing my standard Make Mead Like a Viking presentation, possibly with a few twists. Be sure to stop by the Daggletail Farm booth for some mead soap and other unique soaps while you're there!

Berea (Kentucky) Farmers Market, September 19

Times and details are still being hammered out but suffice it to say that I'll be there in some capacity from 10-12 am (and beyond) demonstrating vegetable lacto-fermentation, with an emphasis on kraut and kimchi. Yes, I do ferment things other than mead!

Mother Earth News Fair, Topeka, Kansas, October 24-25

This is the big one! Tell your friends! Spread the word! I'll likely be at future Mother Earth News Fairs closer to wherever you happen to live but my publisher will quite literally be dropping off copies of the book hot off the press for this event, so it's bound to be a good one. I'll do what I can to make it memorable. Attendees will also have the option of visiting the bookstore and the Chelsea Green booth to meet me (whoo hoo!) and have their own personal copies of the book signed.

Skál to y'all!

June 2015 Book Update

Book Update and Spring / Summer 2015 Workshop Schedule

The book is coming along. My editor and I are working hard on edits, and the design team is working on a cover concept while I finish gathering photos (many of them mine) for what it appears will now be a full-color book with photos throughout. There may even be some illustrations here and there. Unless Ragnarok happens this summer, we're planning on printing in October 2015.

Book Update Newsletter

Make Mead Like a Viking!

Writings and workshops on wild-crafted mead-making

Many of you are receiving this newsletter because you signed up at a workshops. I’ve also added a few folks from my personal contact list who I thought might be interested. If you would rather not receive these emails, simply scroll down to the bottom and unsubscribe. I know how much I dislike receiving emails that I don't have the time for, so I won’t be offended. I promise my updates will be minimal and well worth your while.

For those of you who don’t know, I’m working on my book Make Mead Like a Viking with Chelsea Green Publishing that expands on the information presented in my mead-making blogs with Earthineer.com (as RedHeadedYeti), my homebrewing articles with New Pioneer magazine, and my Make Mead Like a Viking workshops. I’ll be using this mailing list to provide occasional updates and to announce when the book has a release date. I’ll also present information from my readings into ancient history and mythology pertaining to the brewing of mead, ale, and other alcoholic beverages by the Norse and other Scandinavian, Germanic, Anglo Saxon, and Celtic cultures. As time progresses, I’ll likely expand into other areas of the world, as practically every country has an ancient connection with mead. I may even send along a recipe or two.

As a matter of fact, here's one right now for a spiced "small mead". Small mead is a low-alcohol mead (3-5%), takes minimal time and effort to make, and can be drank chilled or as a warmed glogg / mulled mead.

Yeti’s Lazy Viking Mead

Equipment & ingredients: All you need for a one-gallon batch is a gallon jug (glass or food-grade plastic), an airlock (or substitute other options I've listed below), yeast (ale, bread or wild), water, honey, raisins, and whatever flavoring ingredients you desire.

Step 1: Clean your fermentation jug and airlock thoroughly in hot, soapy water and let fully dry. Another option is to make it in a jug 3/4 full of spring water, or removing all but the bottom 1/8 to 1/4 of a gallon jug of raw honey.

Step 2: Mix 1-1.5 pounds of raw honey. To be honest, any honey will do; even the standard store-bought stuff. All the yeast really want are some sugars and enzymes to devour. For optimal flavor and health benefit, go raw and local. The best way to ensure the honey dissolves thoroughly in the water is to place a cap on the jug and shake it like you mean it. You can also use a chopstick or other thin cooking implement to stir it vigorously.

Step 3: Add 1 tsp. of yeast. You can use bread yeast or any yeast designed for an ale. Seriously. This isn't a sophisticated mead designed for long-term aging. It will still be plenty flavorful. If you're already into wrangling wild yeasts and have a starter such as a ginger bug available, feel free to use that. Put the lid back on and shake it again, or stir it with a cooking spoon. Alternatively (my preferred method), initiate a wild fermentation as I've outlined in my Make Mead Like a Viking! - Wild Fermented Mead 101 blog.

Step 4: Here's where it gets fun. I recommend at least adding 10 organic raisins for wild yeast, tannin and nutrients, and a slice or two of orange for acid and a bit of a citrusy flavor. To make a spiced mead (metheglin), work your way down this list, stopping where you please:

1-2 cinnamon sticks

4-6 whole allspice

2-4 whole nutmeg

1 vanilla bean (or 2 tsp. vanilla extract)

1 oz. fresh-grated or candied ginger

Step 5: Once you've added yeast and ingredients, or have initiated a wild fermentation, place a cork and airlock in the opening of your narrow-necked fermentation vessel. Alternatively, a balloon with a small hole poked in it, plastic wrap, or a loose-fitting lid will do. Just be sure to "burp" the lid by unscrewing it a bit every day or so. Do NOT tigten it and forget about it. The best case scenario if you do this is a mead volcano when you open it; the worst case is an exploding mead grenade.

Etc. & Beyond: Feel free to experiment with as many flavorings as you want. I recommend tasting it a week or so after fermentation commences. It won't quite be ready, but you'll get an idea as to whether or not you need to add ingredients for more flavoring. Metheglins (spiced meads) were traditionally brewed for medicinal purposes, or to save a mead gone bad, and could have as many as 50 different flavoring ingredients! Nine times out of ten it will be perfectly fine; if so, leave it alone.

Bottling & Drinking: You have a couple of options at this point. You can wait at least a month after fermentation commences before drinking. Handle carefully to keep the sediment (lees) that has settled to the bottom from mixing in (although lees has plenty of nutrients to impart), and pour or siphon into a drinking vessel. It will be mildly alcoholic, a bit bubbly and plenty flavorful. Or, you can siphon/pour it into some champagne bottles (which you’ll need to cork), flip top/Grolsch bottles, bourbon bottles, or even two-liter plastic soda jugs; and put it in the refrigerator for 3-5 days. Handle sparingly and carefully, as pressure will be building. You should now have a sparkling, effervescent beverage.

More awesomeness

For more recipes and discussions on ancient and wild fermentation, please visit this board, which is a compilation of my various fermentation blogs and articles. Be sure to scroll through the comments on my blogs, as I've provided updates on technique and recipes, and answered questions from fellow Viking mead makers.

While you're there, hang out a while. If you’re not already aware, Earthineer is a homesteading network that connects people locally and nationwide (with a growing international presence) to trade, barter and chat about homesteading, farming, gardening, sustainable living, and all subjects in between. Check us out. We have fun there, and you might even learn something new.

Finally, here are some PDFs of my workshop handouts. The first, my Primitive Mead Making booklet, provides a bit of history and includes two basic recipes to get you started. The second is a shorter handout I made after the Primitive Mead Making booklet that has some updates on additional techniques and hopefully clarifies a few things.

If you are a mead-maker, brewer, or fermentation enthusiast and have any thoughts regarding the techniques I present in these documents, feel free to let me know. I may not have time to respond right away to all inquiries, but I welcome all feedback. Keep in mind that I’m not teaching people how to make mead using modern techniques, but rather my goal is to provide instruction on how to wild-craft mead using local, organic ingredients and (if you so choose) wild yeast. You can make excellent mead using modern methods and ingredients, but my main intention is to set people on the path to brewing locally, naturally, and self-sufficiently so we can come together and take our food system back.

Skál!

P.S. If you would like to visit my little town of Berea, Kentucky this July, I'll be doing several workshops for the Berea Festival of Learnshops. Sign up for mine and check out some of the other offerings while you're there.

Skál!