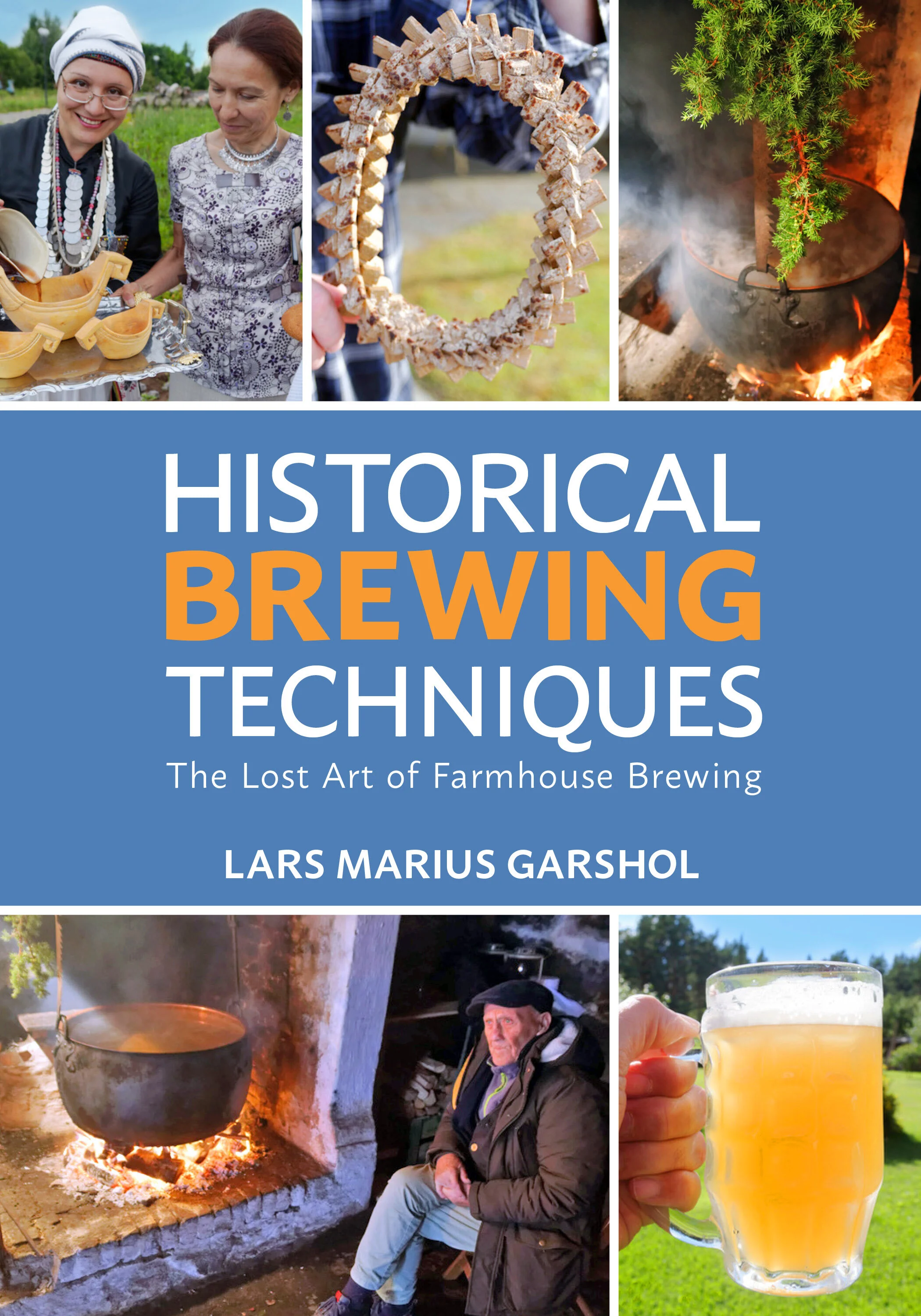

In the first part of this series, I conducted an interview with Lars Marius Garshol, author of Historical Brewing Techniques: The Lost Art of Farmhouse Brewing and the blog Larsblog. Read on for my review of Historical Brewing Techniques and some thoughts it brought up regarding this completely “new” ancient style of brewing.

While Historical Brewing Techniques covers a lot of the same territory as Larsblog, this is by no means a bad thing. Not only is Garshol’s research now in convenient bound form (it’s a sturdy 400-page tome with nice glossy pages for the inevitable beer spillage), but the information from his blog is greatly expanded on. I recommend enjoying it like I did, on the back porch with a beer or three. For my first read-through I made some notes on pages I wanted to come back to when I was ready to start applying the wealth of knowledge contained within, but mostly I just enjoyed the narrative. Even those with little interest in the subject matter can appreciate the book for its engaging combination of travelogue, history, folklore, and fascinating data-driven research. Garshol has uncovered a vibrant brewing and drinking culture that has quietly continued in far corners of Europe (and some not so far corners) while modern, commercial brewing grew to monolithic proportions in much of the world.

Much of what goes on in the craft brewing and homebrewing worlds, even with so-called “farmhouse” styles, relies on tools, techniques and temperatures that are considered irrefutably crucial in creating good beer. (There are definitely some exceptions, though.) Garshol makes it abundantly clear that much of this dogma is antithetical to how people brewed in the days when nearly every household brewed their own beer from start to finish. As a matter of fact, he goes so far as to say that modern commercial brewing and rustic farmhouse brewing should really be thought of as completely separate categories, as they have “evolved separately, drifting apart over many centuries [279].”

Beers brewed by the methods outlined in this book employ vastly different processes and ingredients than commercial beers, and can thus can differ greatly in flavor. If you’re a brewer who is a stickler for the “absolutely necessary” specifics that have been hammered in throughout the modern brewing literature, you’ll need to take a deep breath before delving in. Following is just a sample of the brewing heresies that Garshol discovered farmhouse brewers regularly commit:

A different outlook on cleanliness. Farmhouse breweries can be a far cry from modern, super clean and sanitary commercial (and home) breweries. With many literally being on farms and often using wood as a heating source, the brewing area can often be dank, dusty, and sooty. Except for those who have started incorporating modern brewing into their practices, sanitation with modern chemicals just doesn’t happen. This doesn’t mean that they’re not very aware of possible beer spoilage. Cleaning equipment is an important part of the brew day as with any other brewer; they just employ very different methods. For some brewers, one of the first steps in a brew day is to make up a juniper infusion by boiling juniper branches in water. This infusion is often used as the strike water for drawing out sugars from the mash, but it is also used to clean equipment. While they are very careful about cleaning, farmhouse brewers historically didn’t actually know for sure what kept beer from going bad, so they developed rituals and superstitions that they were sure to follow extremely carefully with every batch. If nearly every beer they made turned out good following these steps, and it worked for their father, mother, grandfather or grandmother (and their ancestors), then it must work.

Preparing a juniper infusion. Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol, from Brewing raw ale in Hornindal.

The wort often isn’t boiled. One of the most fascinating aspects of farmhouse brewing, and one of the core elements that enables such unique flavors, is the concept of raw ale. As a brewer who adhered closely to modern brewing “necessities” when I first read of raw ales, I had a hard time believing that you didn’t need to boil wort when brewing beer. But if you think of the reasons we boil wort when brewing, and look at it historically, this makes perfect sense. For one, we get all of those bitter and aromatic flavors from hops in modern beers such as IPAs through a process called isomerization. Without the proper equipment, and a consistent source of high heat, boiling wort for 60 minutes or more just wasn’t possible historically. While many farmhouse brewers do use hops, they’re not used the same way as in modern beers. They understand their antibacterial properties, but most don’t use them for flavoring. If hops are used, they’re made into a hop tea that is added to the wort while lautering, or even to-taste when drinking. Juniper and various other herbs are known to have antibacterial properties, and were often used instead of, or along with, hops. As Garshol notes, though, there is a broad spectrum as to how these ingredients are used and whether there is no boil, a short boil, or a long boil (of the wort, that is; boiling the mash is also a technique some brewers use).

A mug of raw ale. Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol, from Raw Ale.

A general lack of temperature monitoring and precise measurements. For many of the brewers Garshol interviewed, he was surprised to find that thermometers were rarely used and that they just eyeballed ingredient measurements. In modern brewing, if we want to achieve a particular flavor, alcohol level, and other factors that make for a specific style, it is important to be precise. Most farmhouse brewers aren’t brewing a “style,” they’re just brewing the same type of beer that they were taught to brew by the previous generation. Although there may be nuanced differences between batches, they pretty much make the same beer every time. Because of this, they can judge the proper temperature and ingredient amounts just by look, feel and taste. Some of the brewers Garshol interviewed were perplexed as to why anyone would want to take precise measurements, while others were almost mocking of the modern brewing world’s obsession with precision.

Terje Raftevold brewing by instinct and tradition in Hornindal, Norway. Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol from Brewing raw ale in Hornindal.

The yeast; oh, the yeast… An entire book could be written on the yeast used in farmhouse brewing and how it is utterly different from how pretty much any other modern yeast works. Garshol dedicates a good portion of his book to discussing farmhouse yeast, although he admits that there is much more to explore. His discussion on yeast focuses heavily on the current darling of the brewing world, kveik, but he discusses other yeasts as well. Kveik itself, which simply means “yeast” in some Norwegian dialects, has many variants. Other words used for yeast include gjest(er), gjaer and berm. And then there are the words used in Sweden, Denmark, the Baltics, and other countries. Since each region—even individual farmhouses—had their own unique yeast, there are a plethora of nuances in yeast behavior. Garshol feels he has only touched the tip of the iceberg, but he still covers an impressive amount of ground. If we just consider kveik, some of the ways in which its behavior differs from modern yeast include pitching temperature (often 90 degrees F / 32 C or higher); fast fermentation (full attenuation in as little as 48 hours); viability (many strains have been saved and re-used with little-to-no bacterial infection in non-sanitary conditions for generations—people generations, not just yeast generations); and unique flavors (many contribute citrusy, tropical flavors). The saved yeast isn’t subjected to anything resembling laboratory analysis, and is stored by methods such as refrigerating slurry in glass jars, setting it out to dry and then saving the dried chips in plastic baggies, or even dropping a yeast log, yeast ring or cloth into actively fermenting beer, which is then simply left in a rafter or some other “unsanitary” place to dry until the next use.

Terje Raftevold harvesting kveik after 40 hours. Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol from How to use kveik.

I could go on and on about the many other fascinating aspects of this book, but you’ll just need to read it yourself. In addition to some solid technical how-to and recipes, we’ve got history, folklore, superstitions, yeast-waking screams, oven beers, and some rather interesting malting practices. If you don’t believe me when I say just how unique this book is, how many other brewing books are out there that list as part of a recipe to scream loudly or say the name of every angry dog in the neighborhood? I warrant you there aren’t many…