Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol & Brewers Publications

When I first started researching what became Make Mead Like a Viking what seems an eternity ago, the modern resurgence in historical brewing was just getting rolling. There were some great books out there that set a foundation for my research, but there seemed to be a large gap in good, solid, in-depth empirical research on the subject.

Little did I know that while I was poring through old books, journals and Internet archives—doing my best to separate fact from conjecture—that around the same time a beer enthusiast in Norway was making similar explorations. The difference between us, though, was that…well, I was in Kentucky and he was in Norway. He also had the fortune to luck upon some truly astounding discoveries, finding living, breathing representations of brewing techniques and traditions I was only coming across hints of in dusty old tomes.

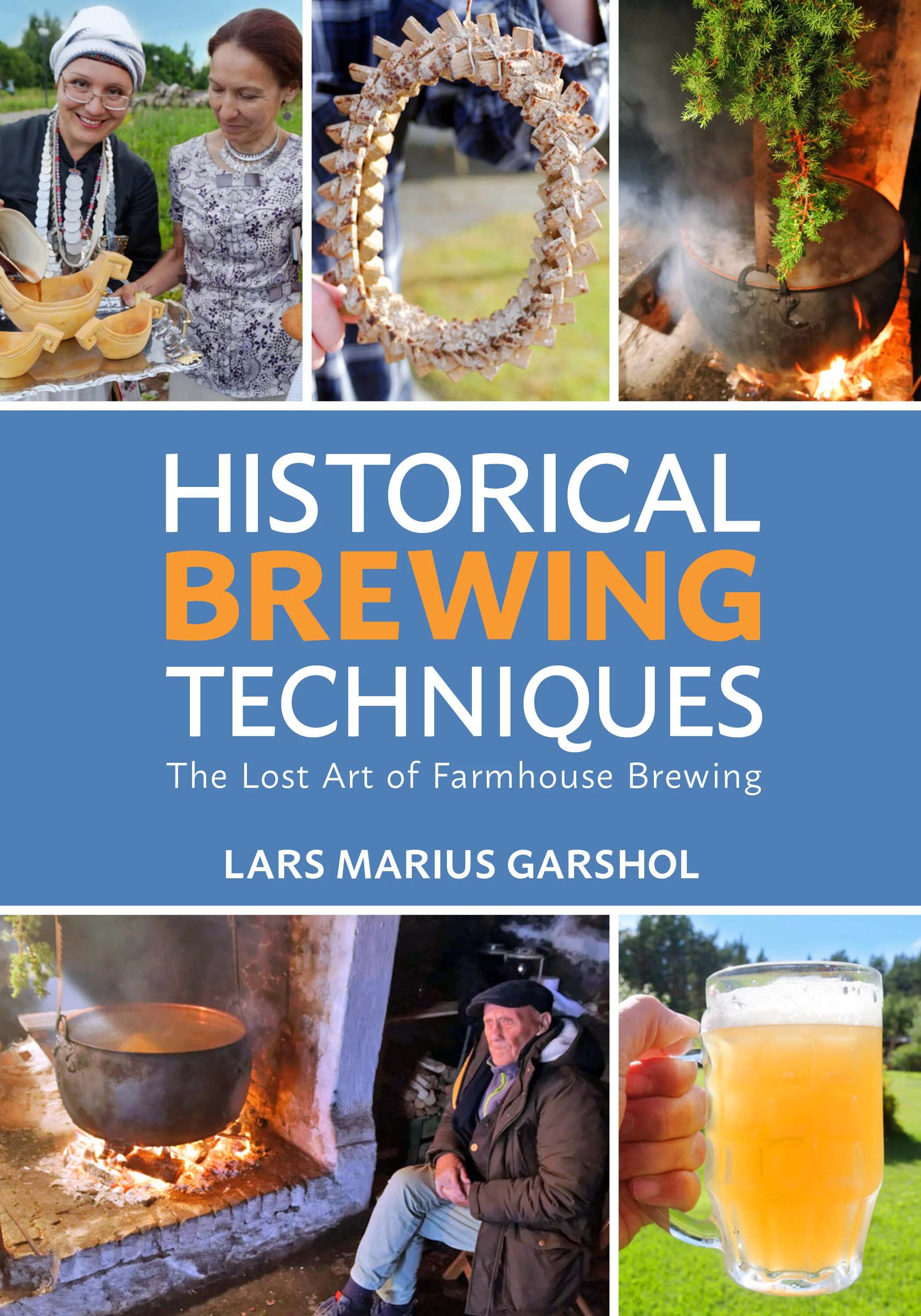

I’m talking about Lars Marius Garshol, who documents his ongoing research in his blog, Larsblog. In moving beyond mead and researching historical beer brewing for my second book Brew Beer Like a Yeti, Larsblog, along with his Finnish colleague Mika Laitinen’s blog Brewingnordic.com, was an invaluable resource. The meticulously detailed research along with the practical experiential tips and photos helped fill in a lot of gaps and set my research in the right direction. Garshol’s new book Historical Brewing Techniques: the Lost Art of Farmhouse Brewing goes even deeper into the world of historical (and modern) European farmhouse brewing.

In this 3-part series, I will be exploring this book and the avenues it opens up for changing the face of modern brewing by stepping back in time. First, I will be presenting my interview with Garshol on his new book, followed by my review of the book; then I will cover my personal explorations in brewing with the techniques, ingredients and yeasts I was introduced to by Garshol and Laitinen. For more on Garshol, please check out my article in Fermentation magazine on the Norwegian farmhouse yeast kveik.

Part 1: The Interview

Photo courtesy of Lars Marius Garshol & Brewers Publications

The research you have done for this book is phenomenal. You approach the subject differently than most beer writers have – verifying everything with data and visiting / contacting brewers to get first-hand knowledge of the traditional techniques they employ. If you aren’t able to verify something you have read or heard an anecdote about you make it clear that more research is needed. What drove you to employ this method of research? Was it particularly challenging to confirm everything you wanted to confirm?

I think in part this is just how I am. I always want to have enough data before being certain of something, and always try to distinguish clearly between what I think and what I know. I don’t always succeed, but when doing research on something I’m of course extra careful about it.

The particular way I’ve gone about researching farmhouse ale was basically forced on me by the amount of data. After the 2014 research trip I got hold of the responses to Norwegian Ethnographic Research’s 1950s questionnaire on farmhouse brewing. That was 181 separate answers, all told over 1200 pages. When I started reading those answers the first thing I noticed was that nobody seemed to agree on anything. Some said men were the brewers, others women. Some said the wort was boiled, others not. Some harvested the yeast from the top, others from the bottom. And so on and so forth for pretty much every single detail.

So I decided to start making a database to see if I could capture and make sense of the complexity that way. Partly that was inspired by the maps in Odd Nordland’s book [Brewing and Beer Traditions in Norway], with differently-shaped markers for different practices in different places. It was really the issue of sweet gale (Myrica gale) that got me started seriously, though. There were lots of claims that sweet gale was widely used in farmhouse brewing, but it was not what I saw in interviews and in the questionnaire responses. What I did see was juniper, which seemed to receive much less attention.

So I started wondering: how can I show this in a convincing way? I quickly decided to capture, for every single account, every single herb they said or believed had ever been used in brewing in their area. Then I started making a table of the results, which developed into what’s now table 7.1 in the book, showing herb usage by country. That table gradually became a very convincing distillation of evidence, and so based on that success I basically expanded the method to cover as many aspects of farmhouse brewing as I could. I’m actually still expanding it, and still adding more data. So the data that’s published in the book is just a small fraction of the data, but much of it I’ve only started gathering relatively recently, so it’s still fairly incomplete. I’m hoping to eventually publish a much more complete and detailed overview.

You discuss flavoring ingredients (herbs, hops, juniper, etc.) that are often brought up in writings on historical brewing. Other than juniper branches and sometimes hops, these ingredients mostly seem to take a back seat, with the grains, brewing technique, and yeast really being the primary focus when it comes to flavor. Am I interpreting this correctly? Do you have any tips for people wanting to brew with any of these ingredients while keeping as close to tradition as possible?

I think that’s accurate, yes. The malts particularly tend to take center stage, but to some extent also process, and to some degree also yeast. Originally the malts, of course, were produced from the grain, the by far most important fruit of the farmer’s labour, and something that was literally venerated as holy and carrying the “power of the earth”. And the malt was generally made by the farmer, so it, too, showed his/her skill as a maltster. So there were many reasons why there was so much emphasis on the malt.

Today, I think the first thing you should do is to accept that you’re probably not going to be able to reproduce the flavour exactly. Especially if you haven’t tasted the original beer, which, let’s face it, very few people have. Because you have a different type of brewing equipment, and your ingredients will probably be different, too. So I think it’s good to have some humility about that. But also not to be too fazed about it. Make the best replica you can, be honest about how it might not be exactly the same as the original, then serve it with pride.

You should of course try to get the same ingredients, but there will likely be differences you can’t overcome. American malts taste different than European ones, same with the juniper, and your kveik is probably a single strain rather than the full culture and so on. But try to get as close as you can, then just accept the remaining differences. You’re making a version from another place, anyway.

I would focus on getting the process as close to the original as possible, and particularly on the carbonation. Carbonation is a huge part of the farmhouse ale character, and something that really sets it apart from modern beer. In general the carbonation should be rather like British cask ale: nearly, but not quite, flat. Of course, selling this is going to be hard, but even so you should keep the carbonation as low as is commercially feasible.

But in the end it’s probably never going to be exactly the same. Belgian-style beer brewed in Norway never tastes like Belgian-style beer from Belgium. And maybe that’s good, because the Belgians brew it the Belgian way, so perhaps we don’t need to copy that. For farmhouse ale it’s different: you generally can’t buy farmhouse ale, so the version you make may be the only one people in your area ever taste. That’s why I think it’s important to be honest that it’s not going to be the same. But I think people should brew the beer, anyway. Just be clear about the differences. An inexact copy is better than none.

One thing you are not hesitant to do is to address myths about brewing that have been perpetuated throughout much of the brewing literature. In many cases you reference something that has pretty much become brewing history dogma and noted that you could find no empirical evidence to support these myths. Can you briefly describe one myth that you could find no evidence to support and another that turned out to be pretty much accurate?

One thing that’s struck me when doing research is how much of what has been said and believed about the history of beer that turns out to have no foundation at all, beyond pure speculation. And how much seems to be quite simply made up. The myth that stone beer is German, and that it is made by using the stones to boil the wort is a classic example of a myth that completely falls apart the moment you start looking closely at it. The myth seems to stem from Michael Jackson’s visit to Rauchenfels in Germany, shown in his TV program. Rauchenfels revived stone brewing in 1982, based on how it was done in Austria. Rauchenfels did indeed use the stones to boil the wort.

So it turns out there’s actually zero documentation of stone brewing in Germany, although I’m sure it has existed. And if you look at the documentation from Austria that Rauchenfels based their process on, it actually says the stones were used in the mash. In all of the documentation of actual farmhouse brewing that I’ve found, from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, and Russia you see the same thing: the stones are used in the mash. This, of course, is as should be expected, since the original motivation for using stones was that people couldn’t afford metal kettles.

If you have no kettle, you have two problems: heating the mash, and boiling the wort. And since farmhouse brewers *still* generally don’t boil the wort, it should come as no surprise that they didn’t boil the wort with them. What’s weird is how widespread this myth still is, and how hard it is to get rid of it, even though it completely lacks a foundation, and also basically makes no sense.

As for a myth that turns out to be true: the idea that people had beer as their every-day drink in the Middle Ages has been hotly contested. But now it turns out that some places people actually drank it every day into the 20th century. The ethnographic documentation of it is just overwhelming so there’s basically nothing to debate. So that myth turns out to actually be entirely correct.

In addition to the techniques and ingredients unique to these brews, there is clearly a rich tradition deeply embedded in all aspects of the process, from gathering and preparing ingredients to drinking the final product. You do a wonderful job of painting a picture of what it’s like to brew according to these traditions. In some cases, the approach to these unique ales is akin to mysticism, superstition, even religion. What are your thoughts on how modern brewers can respect these traditions in their own brewing without veering towards cultural appropriation or simply tossing aside the aspects that don’t work for them? Perhaps another way of putting this is, how should modern brewers approach keeping these brewing traditions alive without directly recreating every single aspect of how the brews are traditionally made?

I think it’s perfectly fine for modern brewers to just brew the beers without worrying about the superstition and other attitudes that used to be part of brewing these beers. After all, that’s what most of today’s farmhouse brewers in these regions do, too. Historically, beer was much more than just beer, but that’s almost entirely over now. The farmhouse ales are intensely personal, more so I think than with ordinary homebrew, but not in any religious or superstitious way. I’ve seen brewers play around with things like the yeast scream, and I think that’s perfectly fine. I don’t see a problem with that.